Introduction

Inflammation is increasingly recognized as a driving force behind heart disease and poor cardiovascular outcomes. The high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) test is a powerful tool that measures subtle levels of systemic inflammation, helping to identify risks even before symptoms appear. By understanding your hs-CRP results, you can take proactive steps toward Heart Health and achieving an Optimal Heart. In this article, we’ll unravel the science behind hs-CRP, its relevance in cardiovascular risk assessment, practical ways to lower your levels, and what your numbers truly mean for your long-term heart health.

What is hs-CRP Testing?

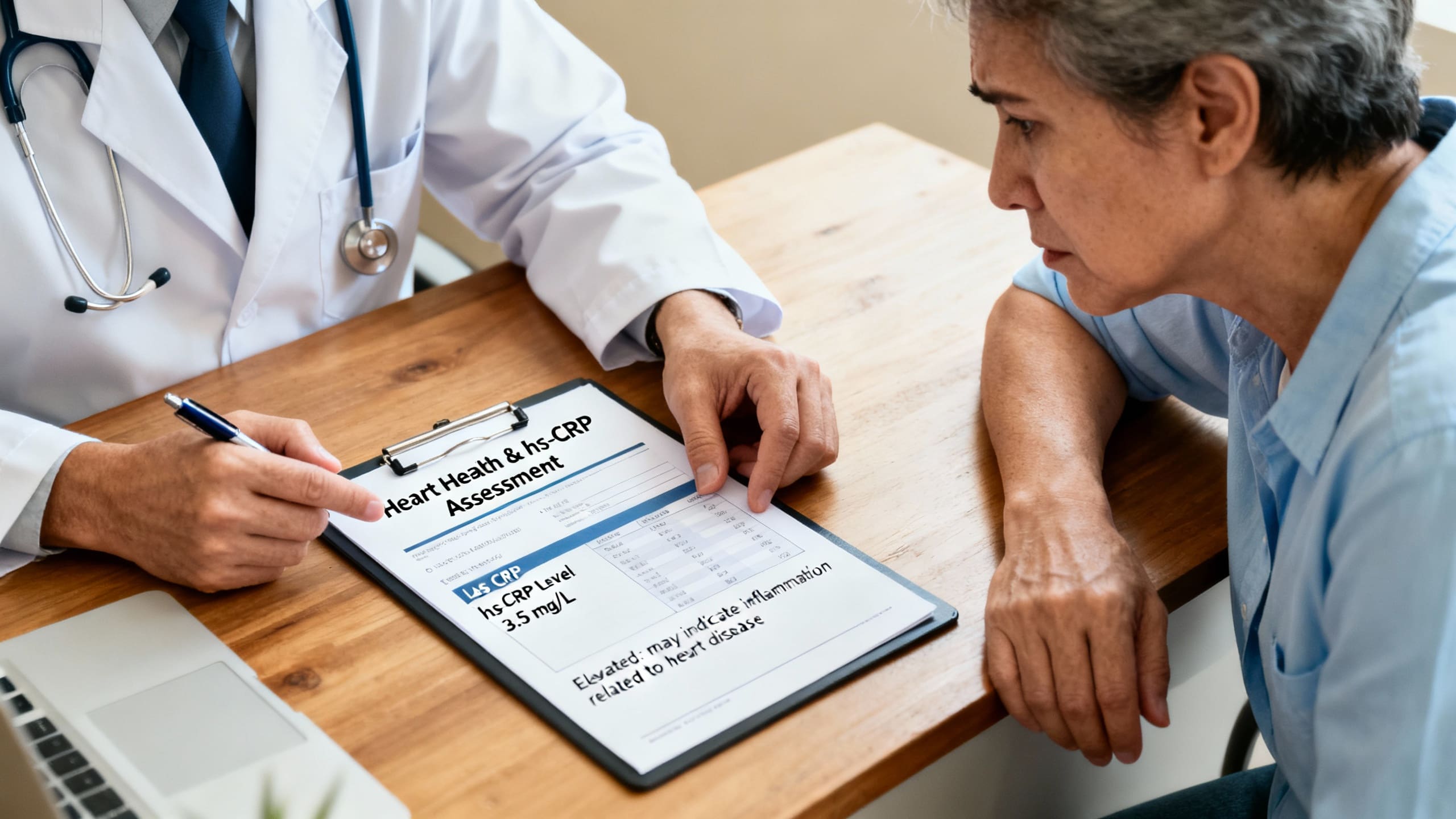

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) testing is a blood test that measures low concentrations of CRP, a marker produced by the liver in response to inflammation. Unlike standard CRP tests, hs-CRP is sensitive enough to detect minor elevations in inflammation linked to cardiovascular risk—not just acute infection or trauma (Ridker, 2002; Pearson et al., 2003).

Originally developed for cardiovascular risk assessment, hs-CRP’s clinical importance has grown as studies confirm that persistent, low-grade inflammation is a key contributor to heart disease and events like heart attack and stroke. This biomarker offers important insight into Heart Health, allowing individuals and clinicians to detect early warning signs for an Optimal Heart.

Benefits and Outcomes in Heart Disease

Research shows that elevated hs-CRP levels are linked to a higher risk of heart attacks, strokes, and other adverse outcomes, independent of traditional cholesterol measures (Danesh et al., 2004). People with hs-CRP levels above 2 mg/L have a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events, making this test a valuable addition to standard risk assessments (Ridker et al., 1998).

Controlling hs-CRP can improve Heart Health by:

- Reducing arterial plaque buildup

- Lowering the chance of clot formation

- Decreasing blood vessel inflammation

- Supporting an Optimal Heart by limiting tissue damage (Ridker, 2016)

Research Insights

Numerous large-scale studies highlight the value of hs-CRP for targeting treatment and prevention efforts in cardiovascular medicine. For instance, the JUPITER trial found that statin therapy not only lowered cholesterol but also reduced hs-CRP and cut heart attack risk in people with initially normal cholesterol but high hs-CRP (Ridker et al., 2008).

Systematic reviews further confirm that lifestyle interventions—such as the Mediterranean diet and regular exercise—can lower hs-CRP and thereby support Heart Health (Schwingshackl et al., 2015). Recent guidelines recommend using hs-CRP alongside other biomarkers for a more comprehensive risk profile, ensuring individuals work toward an Optimal Heart.

Practical Applications

Monitoring hs-CRP helps tailor risk reduction strategies for heart disease.

How is hs-CRP used?

- Routine screening for those with intermediate cardiovascular risk or family history

- Tracking progress with lifestyle or medication interventions

How to lower hs-CRP for Heart Health:

- Exercise: 30–60 minutes of moderate activity at least 5 times per week (Li et al., 2019)

- Diet: Mediterranean or plant-based diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and omega-3s reduce inflammation (Schwingshackl et al., 2015)

- Weight management: Keeping a healthy weight is associated with lower hs-CRP

- Smoking cessation: Quitting smoking rapidly lowers inflammation markers

Supplementation: Omega-3 fatty acids (1–2 g/day), vitamin D, and fiber show mild benefits, although individual results vary (Ridker, 2016).

Who benefits most?

- Those with a family history of heart disease

- Individuals with metabolic syndrome or diabetes

- Adults over 40

- Patients at intermediate cardiovascular risk

Risks & Limitations

While hs-CRP is a strong marker for inflammation and cardiovascular risk, it is not specific—levels may rise with infection, injury, or chronic conditions unrelated to the heart (Pearson et al., 2003).

Testing should not be done during acute illness. Also, not everyone with elevated hs-CRP will develop heart disease—it’s best used alongside other biomarkers and clinical judgment. Over-reliance on a single test could result in unnecessary anxiety or interventions.

Key Takeaways

- hs-CRP is a sensitive inflammation marker that helps predict cardiovascular risk and guide Heart Health decisions.

- High hs-CRP levels are linked to greater risk of heart attack, stroke, and adverse outcomes—regardless of cholesterol levels.

- Lifestyle changes, especially diet and exercise, can effectively lower hs-CRP and support an Optimal Heart.

- hs-CRP results should be interpreted alongside other clinical factors for the most accurate assessment of heart disease risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a normal range for hs-CRP?

Most labs define low risk as <1 mg/L, moderate risk as 1–3 mg/L, and high risk as >3 mg/L (Ridker et al., 2002).

Can I lower my hs-CRP with lifestyle changes?

Yes—exercise, a Mediterranean diet, and quitting smoking are all supported by research as ways to lower hs-CRP and improve Heart Health (Schwingshackl et al., 2015).

Should everyone get tested for hs-CRP?

hs-CRP is most useful for individuals with intermediate or unclear cardiovascular risk, or a family history of heart disease (Pearson et al., 2003).

Suggested Links

- American Heart Association: Inflammation and Heart Disease

- NIH MedlinePlus: C-reactive protein (CRP) test

- PubMed: Search for hs-CRP and cardiovascular risk articles

Conclusion

High-sensitivity CRP testing is a simple yet powerful method for assessing hidden inflammation and predicting your risk of heart disease. By understanding and addressing elevated hs-CRP levels—through lifestyle, nutrition, and medical guidance—you take a crucial step toward long-lasting Heart Health and an Optimal Heart. If you’re concerned about your risk, talk to your doctor about whether hs-CRP testing fits into your personal prevention plan and commit to habits that protect your heart for life.